Perfection is not required

I have a few nutrition coaching clients that strive to be perfect (to the lessons, habits and workouts that form the foundation for the type of coaching I do), but when they are not, everything seems to fall apart. They beat themselves up a bit, and want to quit or restart. I keep trying to express that perfection is rarely required for amazing results. I encourage them to just get back to it, and try to do just a little bit better than before they started. That’s really all that’s needed. But if you are a perfectionist, this is really easy to say but incredibly hard to execute.

The scientists behind Precision Nutrition, which licenses the program I utilize, have researched this extensively. There is a good lay summary here. The programmatic results are stunning even with just 50% consistency with the lessons, habits, and workouts.

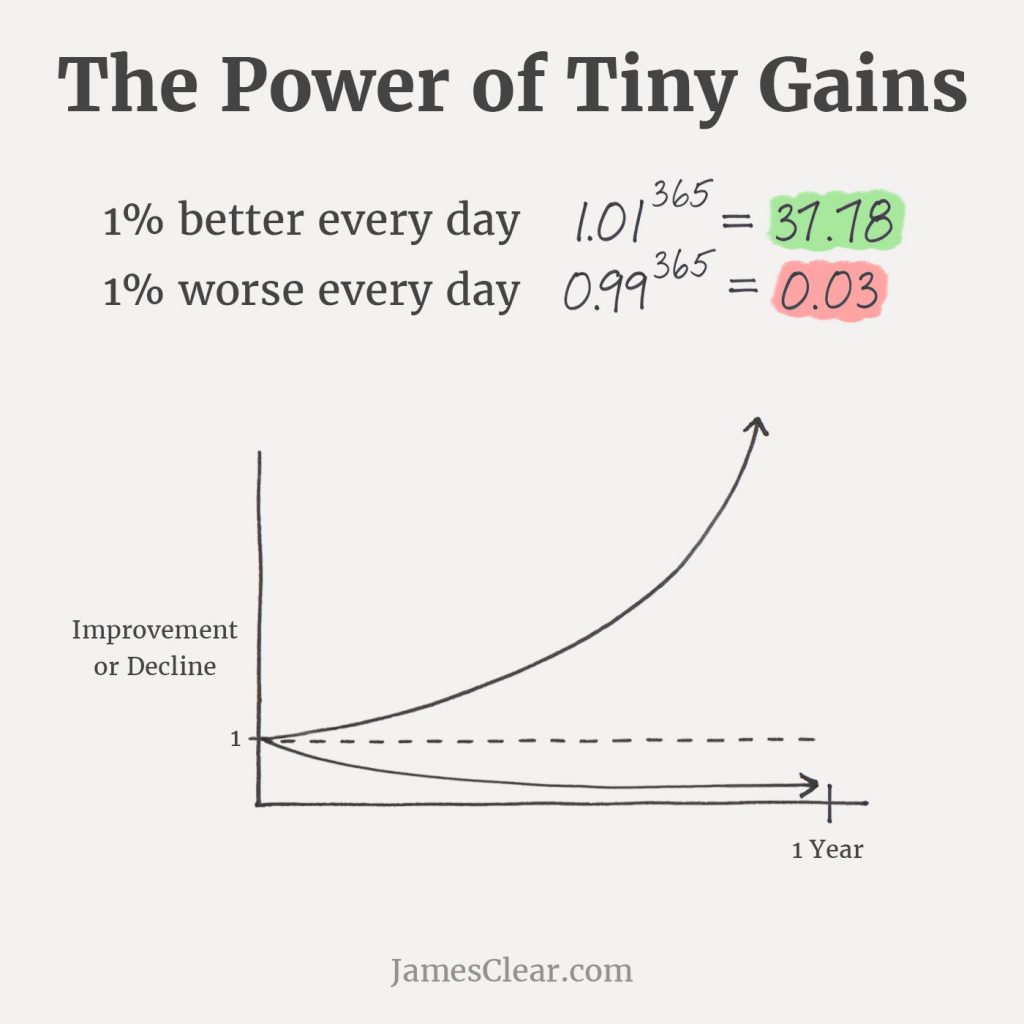

This aligns with James Clear’s research into working on marginal gains.

Meanwhile, improving by 1 percent isn’t particularly notable—sometimes it isn’t even noticeable—but it can be far more meaningful, especially in the long run. The difference a tiny improvement can make over time is astounding. Here’s how the math works out: if you can get 1 percent better each day for one year, you’ll end up thirty-seven times better by the time you’re done. Conversely, if you get 1 percent worse each day for one year, you’ll decline nearly down to zero. What starts as a small win or a minor setback accumulates into something much more.

From James Clear’s post. This is covered in his book Atomic Habits in much more detail.

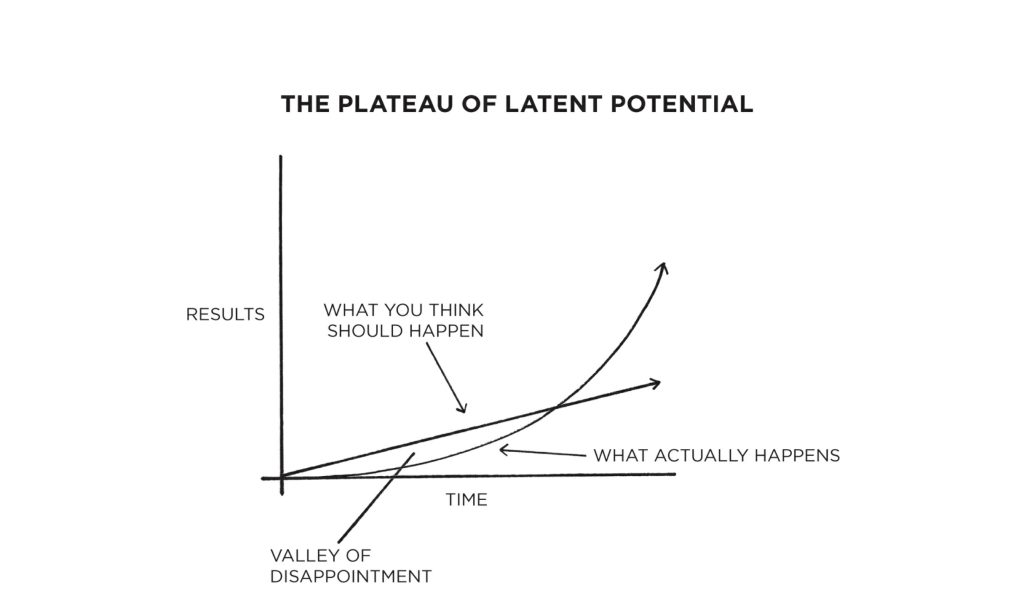

The other piece of this from Atomic Habits, that I found really interesting, is what James Clear calls the Plateau of Latent Potential.

So we often give up, just before we the see the outcomes of all that effort we’ve been putting in.

And it we’d just stuck with our efforts a little bit longer, we’d be amazed and thrilled by our results.

What are you working on? Does it frustrate you if you don’t make progress at the rate you feel like you should? What strategies help you persevere? Or do you just throw in the towel?

Day 17 #BlogPals19

I wonder how many things I’ve left in the valley of disappointment.

Being shaped by the “insta” society – insta-coffee, ready meals, EZ forms, Amazon same day delivery – we want everything fast, in fact we want it now. Who has time to wait?

People go on diets and they want instant results. They forget that it was incremental changes that got them to being overweight – a donut here, a donut there, that extra helping of whatever, the skipped workout session etc. Only to wake up one day and find they are overweight…

Reverse engineer that and do incremental good habits and over time you’ll get where you want to be.

I think i’ll re-visit the valley of disappointment and see what’s there.

C

Clay – I’m with you wondering about this “I wonder how many things I’ve left in the valley of disappointment.”….

How many things did I quit too soon? But on the other hand, I remember learning about Sunk Costs in Business School, which is one of those things that actually gave me the freedom to throw in the towel if success did not seem possible, no matter how much time or $$ had previously been committed. Somewhere in there is a happy place!

Whenever I see an exponential curve, I am immediately suspicious. It is very easy to say “1% better each day,” but crucial to understand what it means. It means that on the 365th day, your improvement day-over-day is 37 times the improvement you made on the first day. It implies that an absolute unit of *improvement* is not just easier but *vastly easier* for you to attain. But in most things human, even though it might start that way, there is a capability asymptote (upper bound) that we can only approach. As a result, the rate of improvement has to go down, and eventually goes to zero.

Thus this approach sets people up for failure. Eventually (and it often doesn’t take very long) they can’t keep up with the exponential and get discouraged – because most of the promised improvement comes late, not early.

Dave, I knew if you saw this that the math would get under your skin! I love “capability asymptote.” I think for me, the thing I like about this perspective (and yes, 100% agree that the progress will plateau at some point), is that small changes can accumulate to the good over time. And I know from my own experience that I’m not suddenly doing dozens more push-ups/pull-ups per set even though I’ve been consistently training them, and trying to do more, for the last few years. As one example. And there is limit to how much faster my running will get. But, I think that striving for incremental improvement is better than letting things slack off incrementally over long periods of time. So I like the concept overall. It’s sort of like compounded interest on a penny graphics. https://www.savingtoinvest.com/power-of-compounding-1-million-now-or/ It doesn’t really work like that but it’s a useful way to communicate the concept.

Feynman emphasized that it is possible to simplify things without making them incorrect or misleading. I suppose that’s anachronistic, but I prefer it. The way I think about this is twofold, first, there is actually a squared term in self-improvement, though even that dwindles after a bit. An example goes like this: If you do pushups every day, and increase that by one each week, by the end of the year you are doing 50 more pushups per day. That is certainly within the realm of feasibility. But the effect on the body is cumulative, so the daily benefit combined with improvement makes the cumulative benefit a function of the square of the time. Don’t boo and hiss at a squared term – I think it’s what this talk is really getting at.

Second, and more important to the long-term, is that making incremental improvement a goal makes the daily base routine a *habit* or *lifestyle*. So by the end of the year, if you’re doing 52+base pushups every day, you have a routine that includes a bunch of pushups. That’s really what is being aimed at, right?

The only tricky part is that motivation being what it is, it is psychologically harder to maintain at 52 pushups every day because the goal is not as stimulating.

By the way: even the compound interest exponential reaches a point of diminishing returns, and we are seeing it today. To receive interest, there have to be borrowers with a way to deploy capital with better returns than the interest rate. There is *so much capital* in the world that interest rates are and have been at historic lows (this has other causes, of course, but this is one). Nobody shows interest rates declining on their compound interest graphs, but that’s what has to happen eventually.